This maintains the upward growth trend in the birds’ population, with two more young, 71 vultures leaving their nests in this part of Bulgaria in summer last year.

This maintains the upward growth trend in the birds’ population, with two more young, 71 vultures leaving their nests in this part of Bulgaria in summer last year. It rewards the constant monitoring of the rewilding area by the Bulgarian Society for the Protection of Birds (BSPB) – Rewilding Rhodopes’s partner organisation carried out in July.

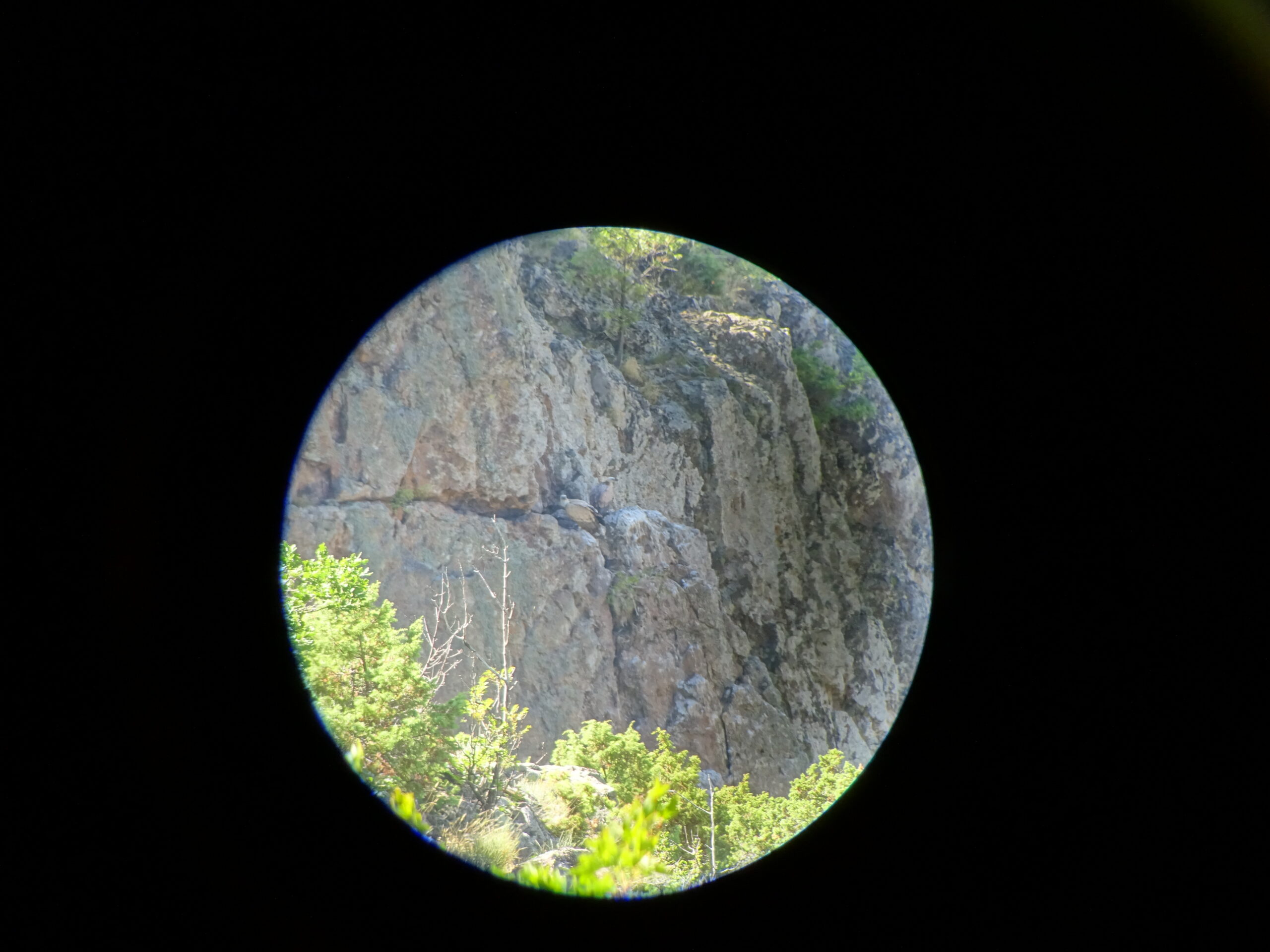

Vulture chicks hatch at the end of March and early April. This spring, 76 griffon vultures hatched in the Bulgarian part of the Eastern Rhodopes. They are then raised by their parents for nearly four months until they are ready to fly, taking to the air for the first time around 140 days after birth. By the middle of summer the young vultures typically weigh about seven to eight kilogrammes; while they are not quite as heavy as their parents, they are the same size, and have all their feathers (although the colouring in juvenile vultures is different to adult birds).

Vulture chicks are often seen practicing flapping their wings while they inhabit nesting ledges. When the wind picks up they often open their wings to “feel” the flow of air – this may be a way of learning how to use the wind when they eventually do take to the skies.

Vulture chicks are often seen practicing flapping their wings while they inhabit nesting ledges. When the wind picks up they often open their wings to “feel” the flow of air – this may be a way of learning how to use the wind when they eventually do take to the skies.

Birds are born with the instinct to fly, but they still have to learn the mechanics of flight. The first flying lessons for vultures are challenging for both parents and fledglings, with the former constantly coming and going from the nest.

In the first few weeks of tentative flight young vultures usually stay close to their nests. They refine their flying skills, learning how to use their wings to take advantage of air currents. It is during this period that we witness atypical vulture behaviour, as these are birds usually renowned for their aerial prowess.

Young vultures often find themselves on the ground as a result of an unsuccessful landings. They then have to climb to a high cliff or other convenient place to take off, making this the most hazardous stage of their development. It is for this reason that most vulture nesting colonies in the Eastern Rhodopes have been monitored and protected since 2017. Those carrying out this work can help vultures in potentially dangerous situations return safely to their nests.