The birds, tagged with GPS transmitters in Dadia National Park in Greece, will offer additional insight into black vulture behaviour and movement on and around the Balkan Peninsula. By supporting conservation measures, this will hopefully reinforce the comeback of this magnificent yet endangered species.

As part of the five-year LIFE Vultures project which began in 2016, five more black vultures were successfully tagged with GPS transmitters in the first week of November. The birds were tagged in Dadia National Park in northern Greece, located in the Eastern Rhodope mountains.

With 11 birds tagged in 2016 (four adults and seven juveniles), this tagging session brings the total number of tagged black vultures to 16. The aim is to tag a further two adult and four juvenile birds by the end of this year. In addition to the fitting of GPS transmitters, every black vulture involved in the LIFE Vultures project is tagged with rings and a wing tag, as well as being measured and biologically sampled.

By offering a unique insight into the behaviour and movement of the birds, the data from the tagged vultures is playing a critical role in the comeback of this endangered species. The Eastern Rhodopes are home to the only breeding colony of the black vulture in the Balkans, with around 20 to 30 pairs breeding annually in Dadia National Park. The number of breeding pairs has remained relatively stable in recent years.

“The satellite transmitters give us an intimate picture of the everyday life of the tagged birds,” says Sylvia Zakkak, Head of Dadia National Park’s Monitoring/Supervision and Application Management Department (which is subcontracted by WWF Greece). “Understanding the vultures’ movements and behavioural patterns means that we can take the best conservation actions to safeguard the birds’ flyways and promote comeback of the species.”

The LIFE Vultures project, which was developed by Rewilding Europe, in collaboration with the Rewilding Rhodopes Foundation, BSPB/BirdLife Bulgaria and a range of other partners, aims to equip around 20 black vultures and a similar number of griffon vultures with satellite transmitters. Last year the Rewilding Rhodopes team fitted seven griffon vultures with transmitters in the Rhodope Mountains rewilding area in Bulgaria, with a further ten griffons tagged this year.

Focusing on the Rhodope Mountains rewilding area in Bulgaria, as well as a section of the Rhodope Mountains in northern Greece, the aim of the LIFE Vultures project is to support the recovery and further expansion of the black and griffon vulture populations in this part of the Balkans, mainly by improving natural prey availability, and by reducing mortality through factors such as poaching, poisoning and collisions with power lines.

The data from tagged vultures, both griffon and black, is fed into a geographic information system (GIS), and this is already leading to some interesting findings. Generated GPS data indicates that most of the birds, if not all, are regular visitors to sites in the Rhodope Mountains in southern Bulgaria and northern Greece. It is known that black vultures often travel long distances in search of food – this is borne out by the movement of Greek birds across the border into Bulgaria.

Some of the black vultures tagged in Greece are venturing a lot further than Bulgaria. GPS data shows that “Helena”, a young female black vulture tagged last year, wandered as far as Romania in the spring, while another bird travelled as far as the Turkish city of Ankara (a distance of more than 700 kilometres) last year.

“Such trips keep surprising us, because they are not that common in black vultures,” says Zakkak.

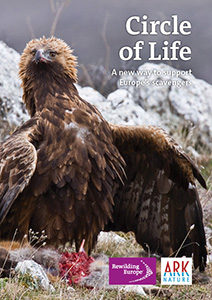

Vultures are perhaps the most iconic examples of European scavengers; the sight of these majestic birds soaring overhead on thermals or feeding at a carcass can be truly captivating.

Two centuries ago, Egyptian vultures, bearded vultures, black vultures and griffon vultures were among the most common breeding bird species in central and southern Europe. Yet the decreasing availability of food, coupled with habitat loss, persecution and poisoning, then saw vultures disappear from most European countries (Portugal, France, Italy, Austria, Poland, Slovakia and Romania). At their lowest point, in the 1960s, there were only 2,000 pairs of griffon vultures and 200 pairs of black vultures left in Spain.

Thanks to reintroductions and species protection, European vulture populations are now steadily recovering. Most European black vultures, of which there are now around 2000 breeding pairs, nest in Spain – Greece is the only southeastern European country holding a breeding population. One of the aims of the LIFE Vultures project is to restore a breeding population of black vultures in the Rhodope Mountains of Bulgaria.

Rewilding Europe, together with Dutch NGO ARK Nature, also wants to help European vultures by encouraging a fresh look at how herbivore carcasses are managed across the continent.

Read more about this new approach, called the Circle of Life, here.